Foreword

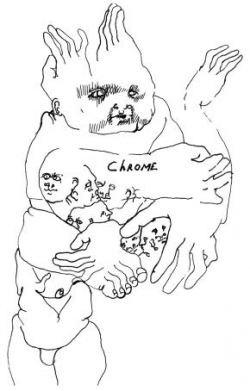

The condition of hearing voices is not always pathological, and many voice hearers do not come forward or tell anyone for fear of being discriminated against. This is not a story about paranormal powers, nor is it fantasy or magic realism. This fictional piece is taken from the real world, the scientific world, and South Florida’s cultural landscape, except my theory about slippers—voices one hears in their head that live on the neuronal roads and in the vast, unknown spandrels of the brain. The reader does not have to believe in slippers, but I do.

Chapter 6

The Junior: Vietnam 1967

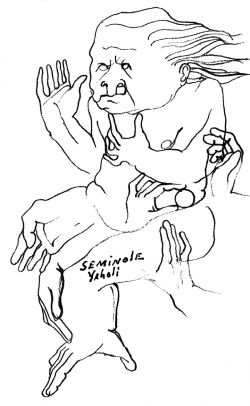

The Junior quit football and college after his one and only semester at West Virginia. “Too damn cold,” he said. He worked cattle for old man Zarnitz, then got into a fight with two men in Okeechobee and killed one. The judge said it was “Questionable self-defense. Right up next to manslaughter. No time in jail if you join the army, son.” So he went to the lead foot farrago of Vietnam.

![]() They were over the jungle-covered mountains.

They were over the jungle-covered mountains.

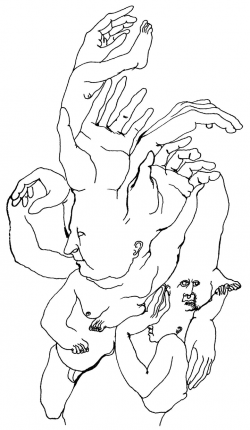

Their squad: the sergeant, The Junior, Freddie Tommie, Pauley, another regular, Suskin the moth man, and three new guys. Whenever The Junior looked at the mountain ranges from the choppers, he always thought they should be like mountains he’d seen in North Carolina, covered in maples and pines and no damn monkeys. He could see where they were going from the Huey, sitting ducks maybe when they landed, even if the hillside was an American firebase and had the green flares on the LZ to signal the area had been cleared. Can’t see anything; can’t hear nothin with this fuckin mix master goin round.

The squad spread out as usual, waiting for the Bell to fly away so they could listen for sounds of the enemy. They were all broke in, no pilgrims; even the new guys had been on other patrols and were aware the law of averages said that while they scratched their necks or cleared their noses they’d be shot as the mission numbers increased.

By now, The Junior didn’t care. He’d taught himself not to care during this American patriarchal political psychosis he was sent to instead of jail, so he stood up with Freddie Tommie and told the sergeant they’d walk in first, as they always did. The other men considered

The Junior and Freddie people who thought they were already dead, the tall muscular cowboy who behaved like a sociopath around gunfire, and Freddie, a reckless but spiritual black Indian who would take the afterlife of hunting grounds any day over this water buffalo shift.

After twenty minutes, the rest followed them in. The Junior was used to jungle. He’d grown up on the north edge of the Everglades, and except for monkeys, mountains, and giant atlas moths on the end of dicks in bathtubs, the snakes and vegetation felt like home.

If the enemy wasn’t waiting for them when they heard the choppers, it could take up to two days for the Viet Cong to move in and engage them. It was guerrilla warfare, contrary to most of the traditional boot camp training for American soldiers, who got the conventional WWII-type training even for Vietnam, and that gave the guerilla-smart Viet Cong an advantage. The Junior and Freddie Tommie had their own advantage. They were swamp raised and knew how to track and hunt. Stay down wind of things.

On the morning of the second day, the squad had circled the area of mountain where they were dropped off and sat down to relax when some VC waiting for them opened up. They shot Pauley off to the right of the group, and everyone else got behind trees, moraines, or anything else that humped a little ground.

Chapter 8

The Blue Goose Gang

In spring of the New Year, all of the Blue Goose bunch went to see Midnight Cowboy and did imitations of Ratso and Joe Buck forever after that. But it was the movie’s theme song, sung by Nielson, the Meistersinger, that Aubrey loved the most.

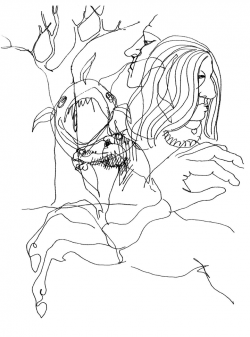

Spring, too, was when the Okeechobee rodeo appeared, cow country’s proudest occasion. The only other thing that caught the town’s eye, three months before that, was Evil Knievel jumping the fountain in front of Caesar’s Palace and busting his ass. Aubrey had drawn a horse called Turkey Track in the first section of the bareback bronc riding. TT, as he was known, had a reputation, and Aubrey knew if he could make it to the buzzer, he’d score well, provided he had done his part of the ride.

Behind the chutes, he sat on one end of a bale of hay, gripped his leather-handled rig, leaned back, and spurred the front of the bale to warm up his legs. Other men he knew from the circuit were doing the same.

“Hey, Aubrey, you got Turkey today, ooh-wee,” a cowboy said.

“Yeah, lucky me.”

“I’d say so. That horse make you some money if you get it done. Ain’t seen you in two years. Thought you might be in ‘Nam with Junior.”

“No, college got me out. I’m gonna sign up, except my mom’s having fits about it. Why aren’t you in?”

The man held up his crooked arm.

“Oh, yeah, I remember. Kissimmee, two years ago. What was the bull’s name?”

“Blurred Vision.”

This was Florida’s cowboy culture, which most Americans do not know exists. People think of the state as only sand bars and beaches.

Florida is the fourth largest cattle state in the Union. Its interior parts are miles of grazing herds, a world walled off from the social dissidence during the sixties taking place in the coastal towns east and west of Okeechobee. Lots of guys in cow country were the real deal, but some were broomstick cowboys and wore boots and snap button shirts to blend in. Only a few from even the real deal would climb down between the steel on something genuinely dangerous with four legs and say “Outside!” to the gate man. Boys on the ranches didn’t like the hippie thing creeping in from the borderlands. They thought it smelled like communism. They did like the idea of fighting for the army and had peace sign stickers on their trucks with the caption underneath, FOOTPRINT OF THE AMERICAN CHICKEN.