Chapter 4

Chapter 4

THE NOT-SO-ONLY CHILD

I’ve been thinking about Aubrey, me, Charles Porter – the hold of his history – the stratigraphy of his life. How years ago, 2001: A Space Odyssey had a huge effect on his free dance – that rising monolith, those apes, the music, the jawbone weapon.

In the beginning for all of us, there was no jawbone, no carnival, no books, no film, no roads, just tracks on the ground – mastodon, ape, cow, human. Later came paths, ruts, piled rocks, blacktops, interstates, tire tracks, soundtracks, contrails, bronze plaques, and destroyed guard rails next to station after station of roadkill cross. That’s what Aubrey Shallcross saw in his seen dreams, those crosses that say someone’s name and “Drive Safely” at the top, instead of “Jesus, King of the Jews.” He saw them when his friend died from a snake bite, when another was crushed by a machine, and as an altar boy when he carried the Solar Monstrance for the priest through clouds of incense. He saw them when Bette Middler’s song, “The Rose,” came through the radio of his truck and he hit a light pole.

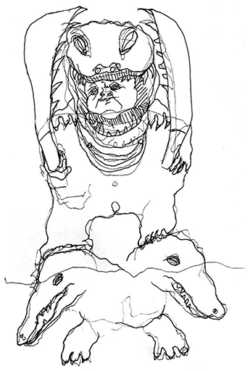

And I’ve been thinking about Aubrey’s other voice, Triple Suiter – the talks they’ve had – Aubrey’s strange house, the taxidermy and mannequins in his living room, his views and opinions of people, and his fascination with the bumper sticker, “JESUS PAID FOR OUR SINS, NOW LET’S GET OUR MONEY’S WORTH.”

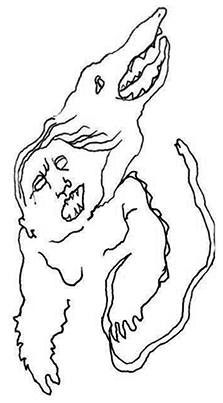

I think about the irony of his last name: Shallcross – his interest in crossroads, cruciforms, four-way stop signs, and his constant struggle to leave Catholicism for some other state of grace. I think about his comatose visions after the man called Carlos shot him and he found himself talking to people on Roman kill trees out in the wetlands, before he went under the wing of a spoonbill to dream.

It’s been two years since Carlos put a bullet in Aubrey’s head. Carlos, who came to kidnap and rape Aubrey’s love, Christaine. Then chaos and that bullet. For a moment, Aubrey thought he was in a movie, thought it was the dreaded “country visit” from A Clockwork Orange or In Cold Blood. Seconds later, Christaine and her father killed Carlos. Now everyone is trying to heal. A metal plate covers the hole in Aubrey’s skull; his hair has grown back. He and Christaine have a five-year-old son named Drayton. For Aubrey, there is too much free time, and he feels some-thing has been rearranged in his brain, maybe from that bullet. He still schools his horses in the mornings and trains with Christaine’s father, the riding master. In the afternoon, capillary thought takes him to a big room, a capacious cyclorama in his mind with a version of the Eiffel Tower in the middle of a cane field. Around the tower he flies, permuting things into a proto-corpus that pleas-es him, pushing on the elan of objects, music, books, film, and thoughts from his storied life, especially when that part of his brain he calls the “Mess Hall” comes and he is molested by agnosticism and existential cramps.

I remember when his mind split, after his father was dragged off a tractor by a flame vine – killed. The bohemia of his life in that wilderness after, the wildness of his twenties and thirties, the band he was in and Leda, his young wife – their happiness, their cross threads, her drugs, their end.

I think about The Blue Goose, a bar based on the short-sleeve shirt. The friends went there to laugh and sing around a table in the 70s, doing their “Oh, yeahs” from the movie Seven Beauties. So much happiness in those times until Leda left him, his friend The Junior died, and the other things that happened after that generation of star flies, bar flies, and Super Fly began to age. Now he only has one friend from the old group, John Chrome, and at age fifty, after all that has happened, two beatitudes remain – Christaine and his boy Drayton.